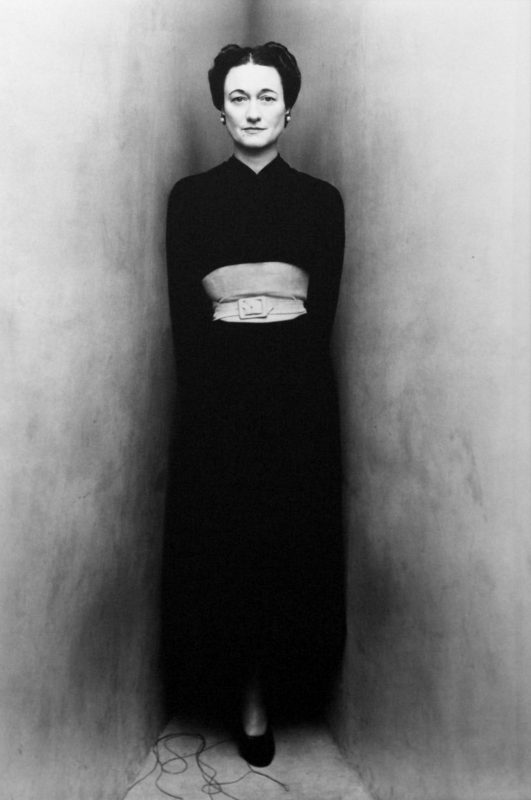

Duchess of Windsor, New York, 14th July 1948

IRVING PENN

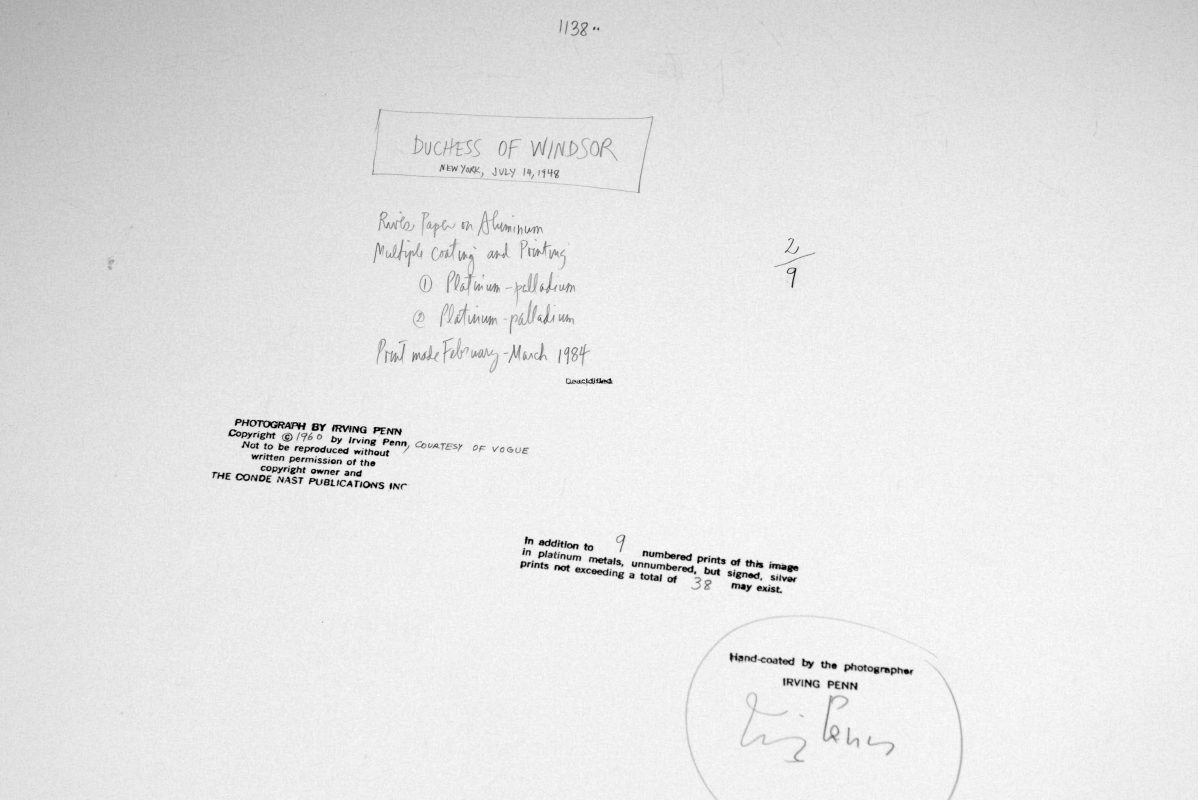

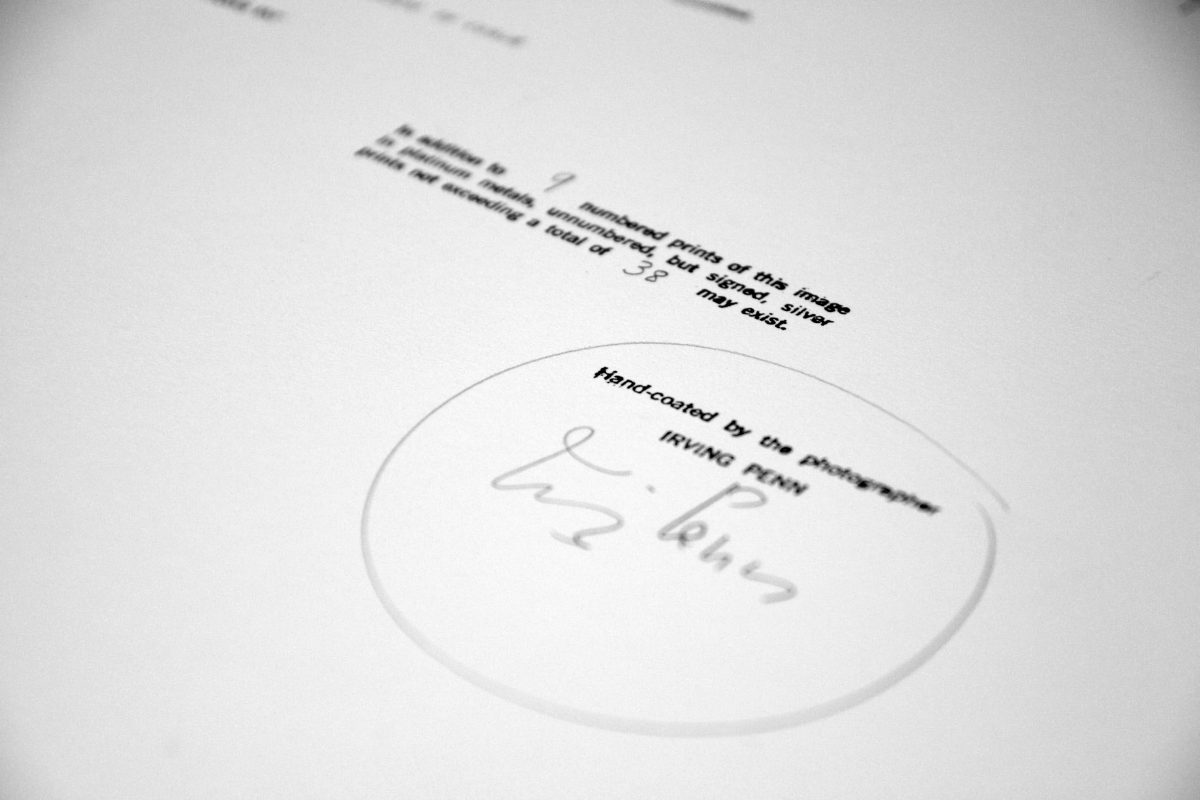

Signed, titled, dated, numbered, inscribed with 'Vogue' credit and stamped with Penn/Condé Nast copyright and edition stamps on reverse of mount

Platinum palladium print mounted on aluminium, printed 1984

19 x 12 1/2 inches

From an edition of 9

SOLD

Irving Penn’s contribution to photography, including portraiture, still-lifes and fashion photography have made him one of the most acclaimed photographers in the history of the medium. His decades long career created some of the most important photographs of the twentieth century.

Penn began working with Vogue in 1943, then under the directorship of Alexander Liberman. This would prove to be one of the most fruitful relationships with a photographer in the history of the magazine. Penn worked with Vogue over several decades, but it was in the first years with the magazine that he developed his unique approach to studio portraiture. Rather than create elaborate props or styled environments that reflected the sitter’s personality or profession, Penn photographed his subjects against stark backdrops and with very little theatricality. This broke with many twentieth-century conventions of the genre.

This portrait of Wallis Simpson, Duchess of Windsor, was taken the year after Penn had conceived of his now renowned angular, cornered set, created by the intersection of theatre flats that he had in his studio. Using tungsten lights to simulate daylight, he created simple portraits that focused solely on their subjects. Commissioned to photograph the Duchess of Windsor in July 1948, Penn depicts her in a precise, sculptural composition. Penn creates receding perspective and draws the viewer into the image, through the orthogonal lines of the theatre flats that guide the viewer’s gaze directly to his subject. Simpson creates an abrupt end to the dominant diagonal lines of the photograph with the strong verticality of her posture. She is depicted in an elegant black dress with a white sash that reflects her glamorous persona, highlighted against the stark surroundings in which she is photographed.

Rather than create elaborate props or styled environments that reflected the sitter’s personality or profession, Penn photographed his subjects against stark backdrops and with very little theatricality.

Penn has said of portraiture, ‘In portrait photography, there is something more profound that we seek inside a person, while being painfully aware that a limitation of our medium is that the inside is recordable only insofar as it is apparent on the outside.’ Penn was fascinated by revealing the psychology and personality of his sitters. Without an elaborate and stylised set design, Penn denied his subjects the opportunity to project a character of themselves, rather his photographs reveal a more truthful representation of their personality.

Penn was as highly regarded for his printing as he was his photography. In particular he was fascinated by the platinum-palladium process, a Victorian method that was considered antiquated until Penn helped to revive its popularity as a technique. This print was made in 1984, and is a fine example of the tonal virtues of platinum-palladium prints.